Neural Audio Synthesis#

A Brief History of Audio Synthesis#

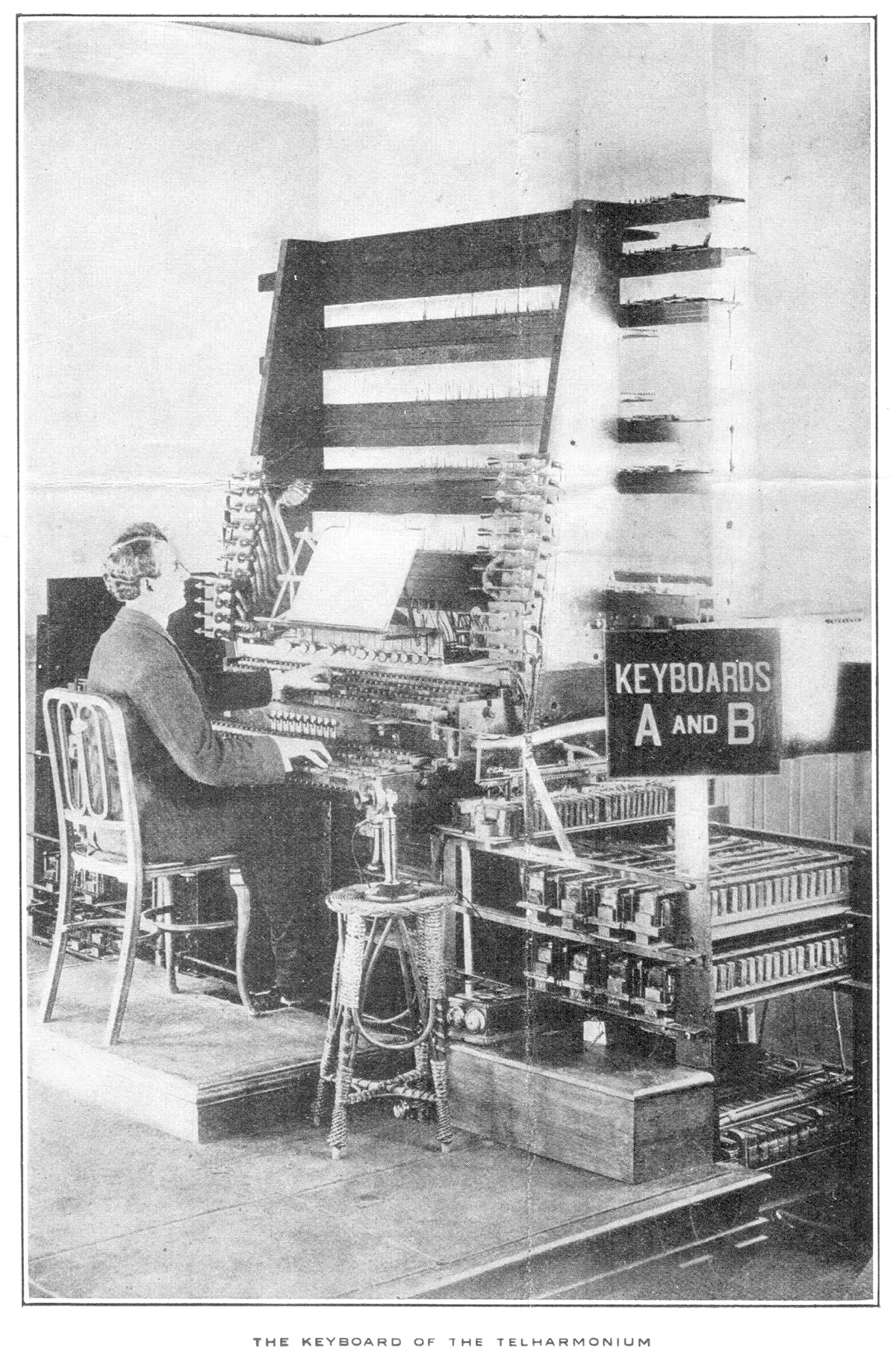

Audio synthesis, the artificial production of sound, has been an active field of research for over a century. Early inventions included entirely new categories of musical instrument, such as Cahill’s Telharmonium and the Theremin, and the first systems for artificial speech production, such as Dudley’s Vocoder.

Fig. 1 Thaddeus Cahill’s Telharmonium was one of the first musical instruments to produce sound electronically — an early synthesiser.#

As electronic components became smaller and more reliable, synthesisers followed suit. During the 1960s, Moog & Buchla’s designs laid the framework for new categories of electronic musical instrument, which went on to define entirely new genres and aesthetics. At the same time, the first digital vocal tract models [KL62] were produced. The latter part of the 20th century saw a proliferation of research into digital methods for sound synthesis, built on advances in both digital signal processing and numerical methods. Whilst once the purview of specialist research laboratories and pioneering music composers, commercially available hardware and software synthesisers placed the technology in the hands of a much wider array of users, from touring bands to at-home hobbyists. Today, it is possible to simulate entire analog synthesisers on even modestly powerful personal computers.

applications of audio synthesis have since come to permeate daily life, from music, through voice assistants, to the sound design in films, TV shows, video games, and even the cockpits of cars.

Fig. 2 Arturia’s software model of the Sequential Circuits Prophet 5 simulates the behaviour of individual electronic components to produce a replication of the sound of the original.#

Deep Learning Arrives#

In recent years, the field has undergone something of a technological revolution, with the emergence of deep learning as a viable tool for audio synthesis. The publication of WaveNet [vdODZ+16], an autoregressive neural network which produced a quantised audio signal sample-by-sample, first illustrated this possiblity.

Over the following years, new methods for neural audio synthesis abounded, from refinements to WaveNet [vdOLB+18] to the application of entirely different classes of generative model [EAC+19], including generative adversarial networks (GANs), variational autoencoders, flow-based models, and more recently denoising diffusion probabilistic models.

Nonetheless, audio signals are inherently high-dimensional, exhibit multi-scale temporal inter-dependency, and have a strikingly non-intuitive relationship with perception — characteristics which are decidedly non-trivial to learn directly from data. These properties underlie a number of challenging-to-resolve phenomena when modelling audio with neural networks. Upsampling layers, for example, crucial components of workhorse architectures such as GANs and autoencoders, were found to cause undesirable signal artifacts [PPCS21]. Similarly, frame-based estimation of audio signals was also found to be more challenging than might naïvely be assumed, due to the difficulty of ensuring phase coherence between successive frames, where frame lengths are independent of the frequencies contained in a signal [EAC+19].

Today, well-trained GAN and diffusion vocoders are capable of overcoming these issues in certain domains, given sufficient model capacity and quantities of data. However, parallel line of research also emerged, which sought to address them by instilling models with inductive biases rooted in our prior knowledge of the properties of audio signals

A parallel lineage of research emerged, however, which seeks to reduce the burden on models to learn these signal characteristics by constraining the model’s outputs so that they were already biased towards them. This is achieved by directly incorporating signal processing operations with known behaviour into the model, which we shall discuss in the next section.